As part of MAP, from 15 to 30 November 2023, we welcomed Clémentine Labrosse (she/her), a French publisher, journalist, and author who is committed to investigating artistic practices from a feminist and queer perspective, in residence.

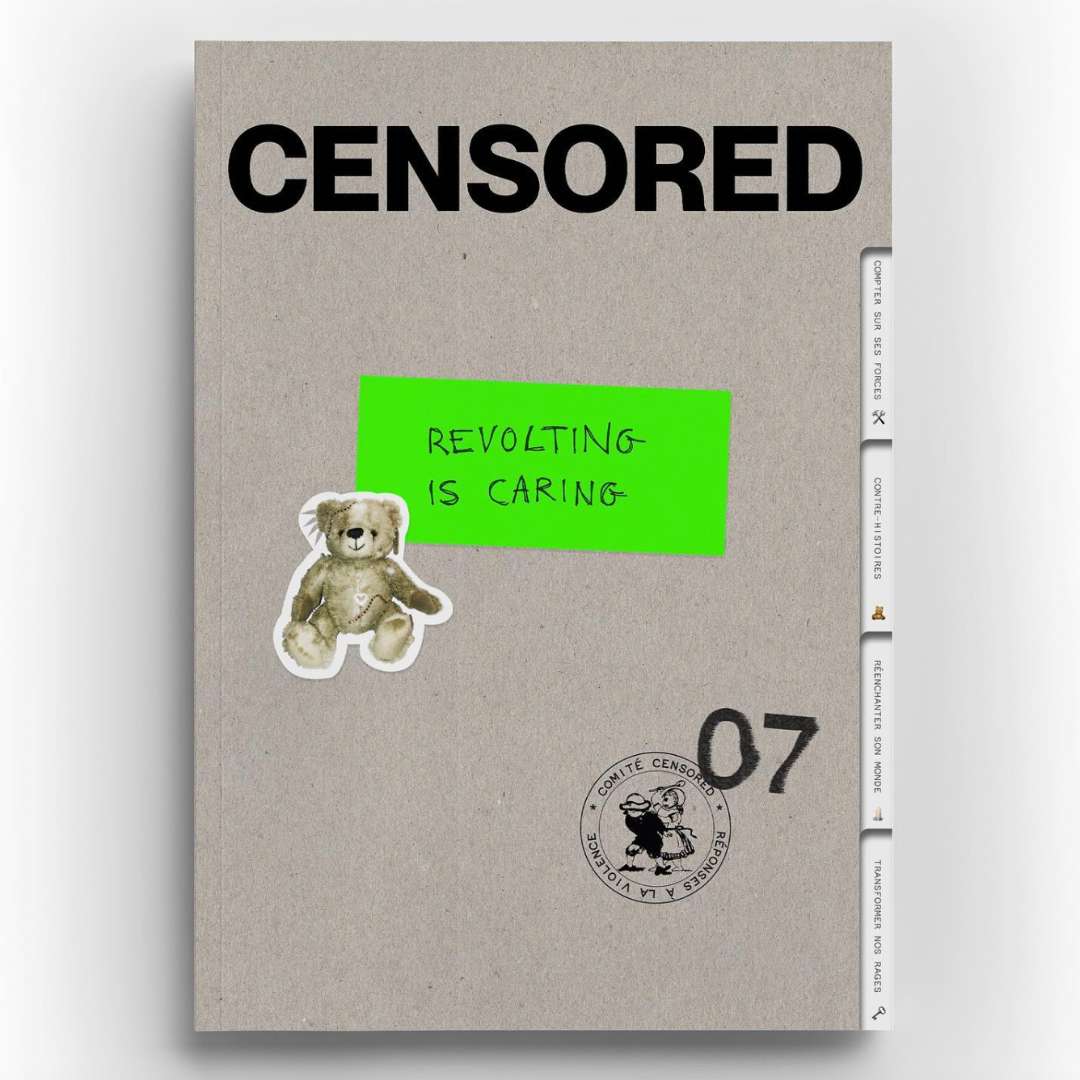

In 2018, with her sister and artistic director Apolline Labrosse, she founded the independent Censored Magazine, which aims to document contemporary artistic expressions through the struggles of the emerging literary and creative scene and the work of recognized activists.

Her writing uses imagination and auto-fiction to explore the political and collective dimensions of spirituality, the intimacy and richness of our inner worlds, the magic of biodiversity, and freak and rural culture. Her practices start from the desire to show that every 'birth of self' is rooted in the complexity of the safe yet violent environment surrounding us, of verbal and sensitive languages, and the great challenge of overcoming the isolation and habits cultivated in our capitalist society. More generally, it seeks to investigate the poetic dimension of things and their revolutionary power, sometimes beyond the rational world.

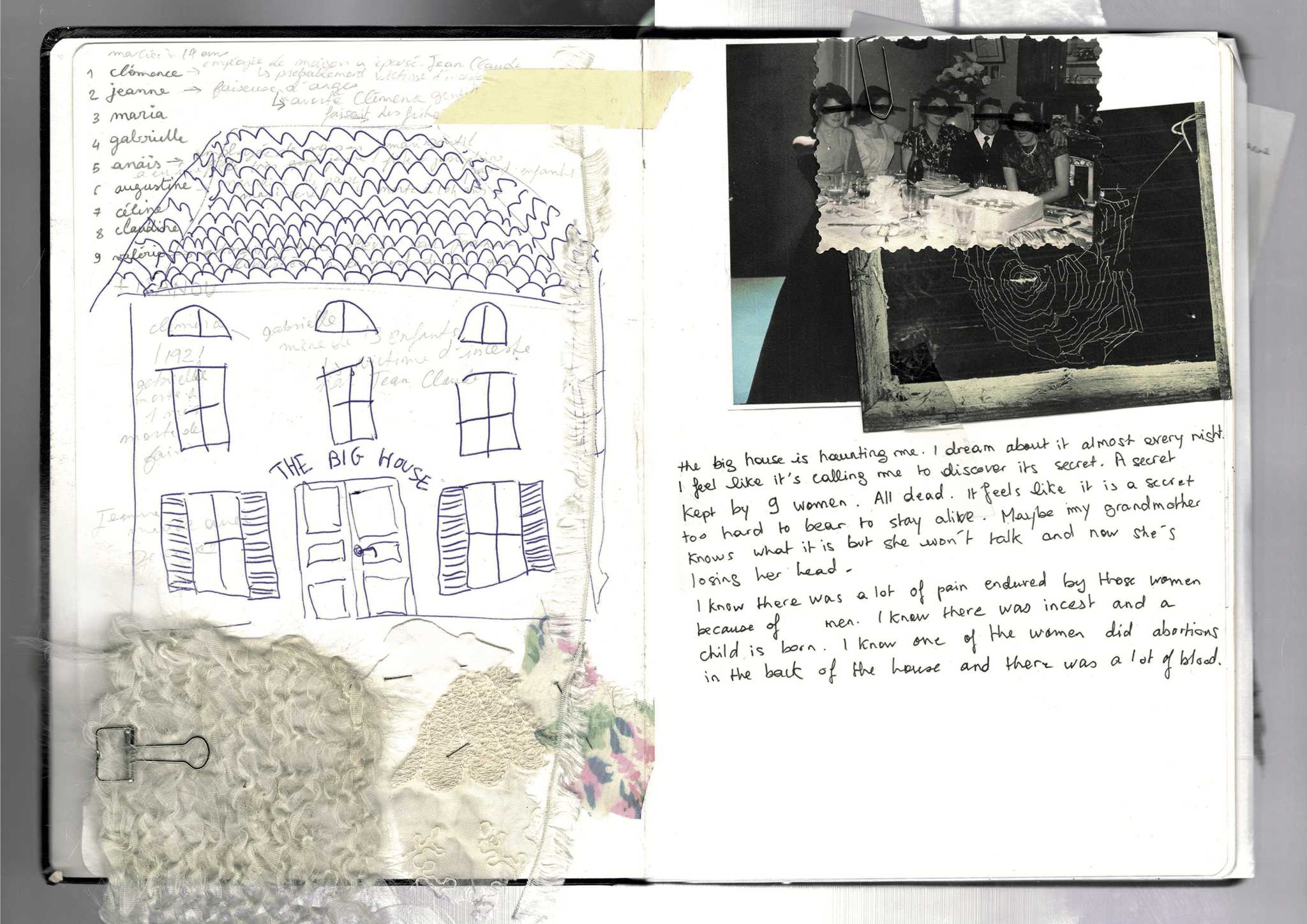

While researching on the Amalfi Coast and in Campania, Clémentine began work on her first book, «a fantasy tale, a huis-clos set in a mysterious house, populated by ghosts, women, and friends engaged in a common quest to discover an underground network. It will be about saving the last seeds and family secrets and living together.»

Conceived as a vast and intimate political investigation, the story blends dialogue with excerpts from the protagonist's diary, documenting these decisive hours for her history and the future of the land that nurtured her childhood: "What survives us as we change by transforming the world?"

Clémentine's research takes different approaches to celebrating death, funeral orations, and the power of plants and the living.

We interviewed her!

Marea: Hi Clémentine! Tell us who you are, what you do, and what you worked on during your residency on the Amalfi Coast.

Clémentine: I am Clémentine Labrosse, journalist, editor, and author of a soon-to-be-published first book I started writing here in Praiano. Five years ago, with my sister Apolline, I founded the French magazine Censored. I take care of the texts, and she takes care of the pictures, so we complement each other. It is a magazine that deals with a theme related to rather political and radical feminist issues through the involvement of artists and activists. There is also a large section dedicated to emerging literature, perhaps closer to my heart.

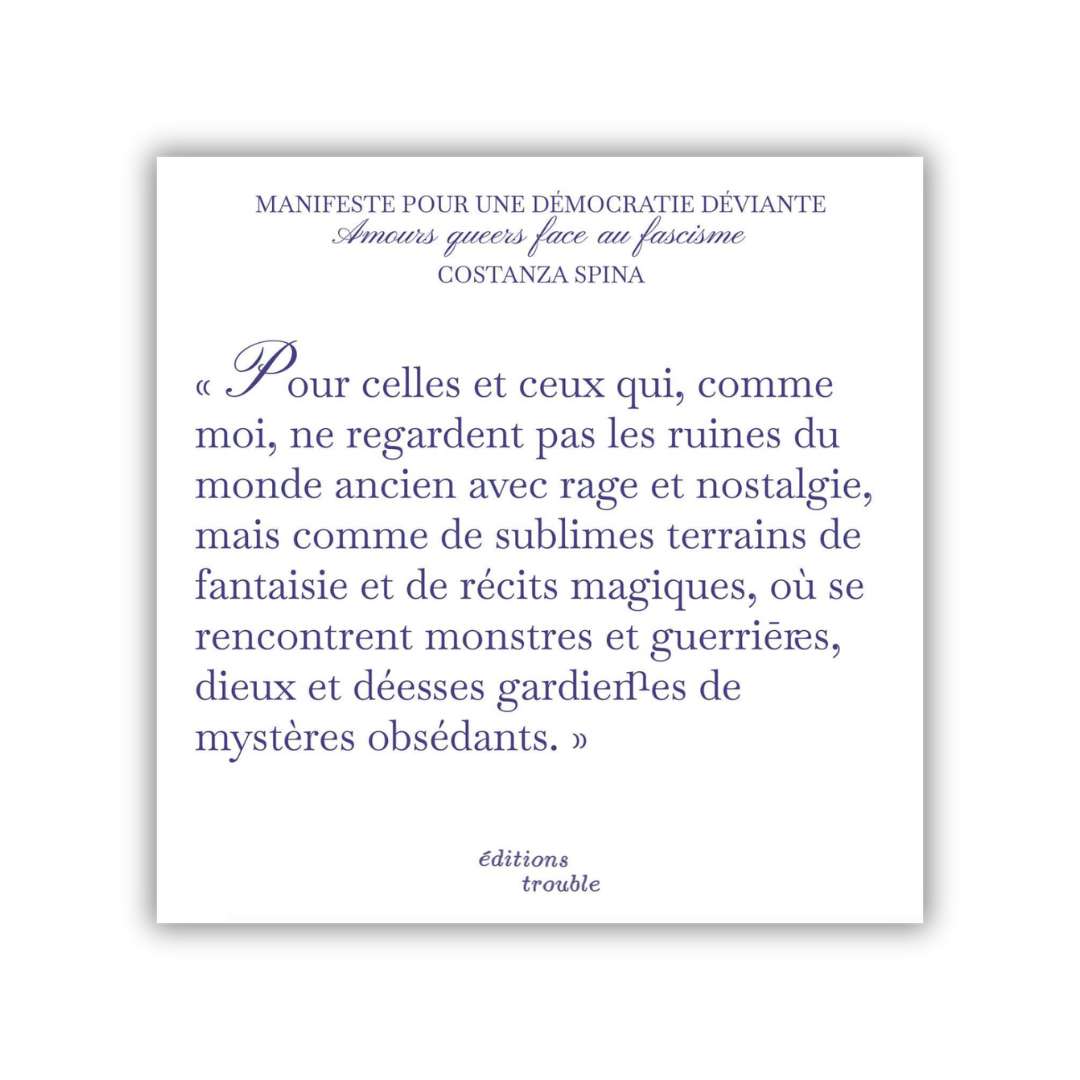

Also, more recently, Apolline and I created Editions Trouble, an independent publishing house. So far, there is only one publication, which came out last June and is entitled "Manifeste pour une démocratie déviante. Amour face au fascisme" by Costanza Spina, who also created a very engaged independent queer media in France.

The idea of writing a book started long ago in my head, and I have been taking notes everywhere for years. My sister and I are carrying out a gigantic investigation into our family history, especially the history of women. We realized that they have experienced a significant amount of patriarchal violence, and that is why we created Censored.

In Praiano, not only I had time to reflect, think, and structure everything I wanted to tell, but I also made contact with local people who have many connections to my family history. I arrived here with something intangible: many notes on my phone, in notebooks. Here, I could organize my book, finding the structure and characters.

I was able to write parts even though it was the beginning. But when I leave, I will have a huge draft, something I can work on because everything happening here is strange. I'm very alone with my thoughts, but it's also very intense.

I think that when I come back, it will come out, and it is very accurate what Ciro Ciretta said when they arrived here, and I could talk to them. They advised me not to write too much in Praiano but to wait. There is a before and an after Marea, in the sense that there is such an intensity of thought around this book project that, in my mind, most of the work was done here.

There is restlessness in all this because I am writing my first book, which is also fiction, almost science fiction. Before that, I spent about eight years in Paris, which was a place where I approached activism and feminist issues. It allowed me to deconstruct myself as a woman and as a person.

Marea: Are there literary references or personalities that are inspiring you in writing your book? Is the residence in a place like Praiano, far from the centers of metropolis, playing a role in this research?

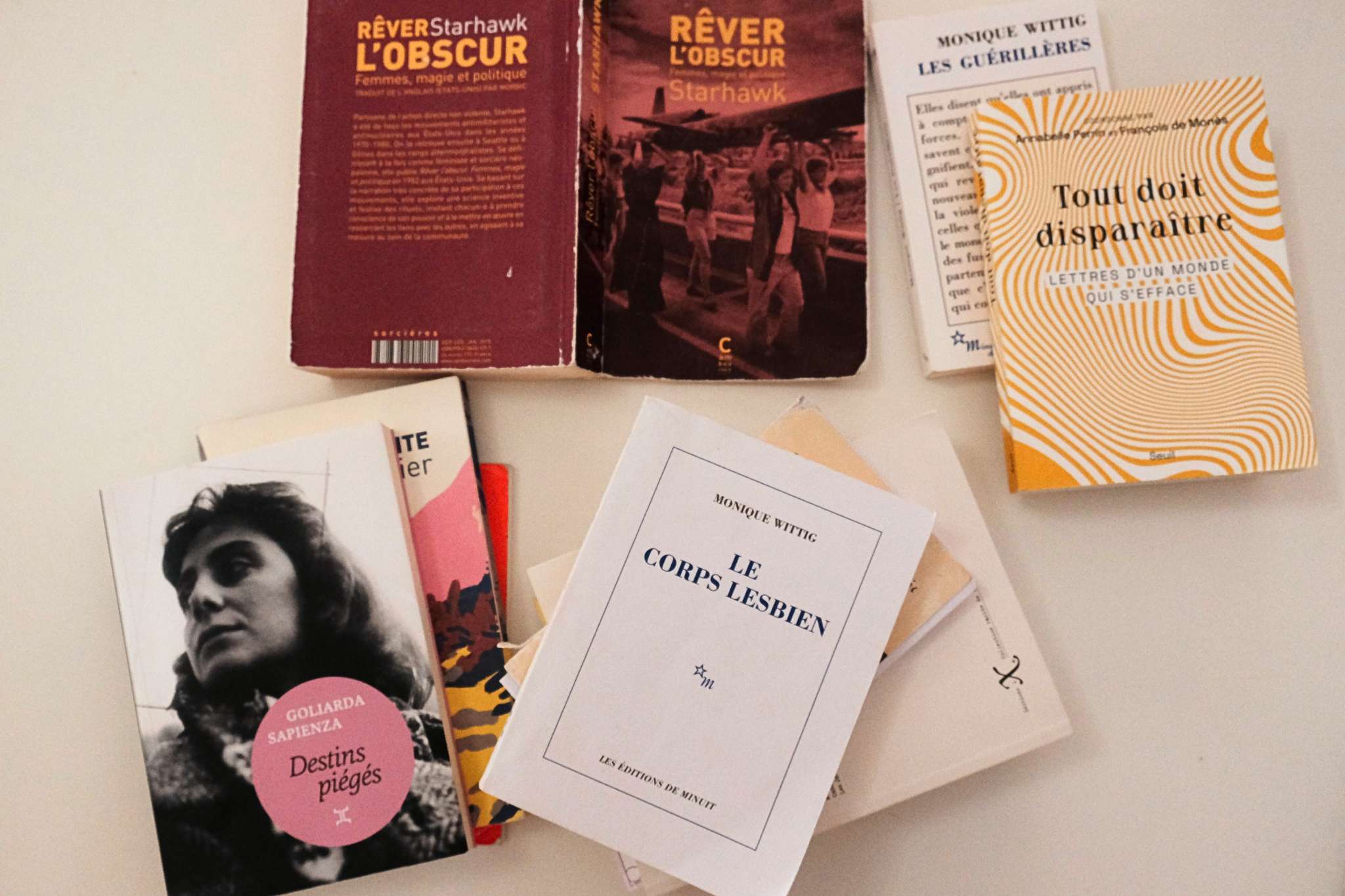

Clémentine: This book will be a work of fiction and be like a dream in a room, but there are also moments outside this extensive family home. I was inspired by Starhawk's Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex, and Politics and all these links between political magic, collectives, sorority, and adelphité. How do we reflect profoundly and intimately? How to rebel? How do you revolutionize yourself, and how do you do it as a collective? Indeed, one cannot revolutionize oneself without connecting oneself to a territory, other women, or other people. These things are completely inseparable, and this is one of the things I have been defending for a long time. And I am even more sure of it after this experience.

I see a lot of echoes between these aspects and the importance of returning to more local places like Praiano. In this sense, I was inspired by the French activist and political scientist Fatima Ouassak. She used to say that she only thinks about local struggles.

And it's funny because CiroCiretta used to say the same thing: these people don't know each other at all, but there really is this shared desire. The idea of starting from the places we know so that we can finally fight and transform the world, and this is what I intend to do through imagination.

Let us focus on the most local areas and re-enchant our world. I am not talking about a fairy tale when I say 're-enchant'; I am talking about recreating a connection with our land, neighbors, and the people we know and reclaiming a life other than one based on capitalism.

This is very present here in terms of reflection. These are things I have also been able to discuss with you. Why return to a place like Praiano? Why not research starting from the big cities? Why not research on power? There is a whole reflection on how to turn things around. It is also essential to stay at home sometimes. I also connect with the book and its subject matter because a lot happens in a house. Then, often, the greatest revolutions happen within ourselves.ə.

Marea: You resort to imagination and fiction for your book. Why?

Clémentine: I do it because it gives me a chance to get away from the rational and access the invisible, which is much more potent for me.

After MeToo, there was a great need to understand, talk, and analyze from a political point of view. At that time, I became very interested in the question of narrative and the imaginary in all its parts.

In fact, there is a lot of dystopian material in the history of feminist fiction. I often think, even with friends or journalists, people I work with, about how to end dystopia, always imagining the worst or the end of the world, even if it is cathartic. I'm interested in getting closer to reality over time so we can cling to it. So it's a little less catastrophic and more concrete, but we make it more poetic.

I think, for example, of The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, which was a very inspirational bestseller. At a certain point in my life, it helped me a lot as well, but I'm actually a bit fed up with reading things where women become slaves, or where we see the end of the world, or I don't know, think about the abortion issue. It is always one of the first things to fall when there is an authoritarian government.

So, I would like to look for something closer to reality. This is what we can bring positive and what we can do with trauma and violence. Turning the possible into the really possible. For that, someone has interested me: Ursula Kroeber Le Guin, a feminist science fiction writer, and Octavia E. Butler, a science fiction writer.

That is what I have been looking for, between what is possible and what is not. There are too many new worlds. But actually, it is more important to make it more circumscribed and smaller so that it has an impact and also makes the imagination work better.

Marea: You have repeatedly mentioned the name of CiroCiretta Cascina, a profound connoisseurə of Neapolitan popular culture and femminiellə. CiroCiretta is also the star of the documentary "Chic and Fabulous" by Roman director Andrea Fortis. Can you tell us how this encounter went?

Clémentine: In CiroCiretta, I found a lot of inspiration for one of the characters in my novel; it starts with the idea that there are people on this earth capable of making you more sensitive and who really bring poetry into the world. How do we leave rationality behind? How do we talk to our emotions? I think it will have a significant influence on my book. The character in my novel is a key figure; he is a bit of a messenger from this village but also a bit of a UFO because of all this ambivalence.

I take inspiration from Leta; I take inspiration from other people. Like CiroCiretta, as said they are a person who brings a lot of poetry into the world, but he is also a very radical figure. It's also a way of fighting against the somewhat dull side of cities, like re-enchantment. Here is someone who enchants.

Moreover, through Andrea Fortis's documentary, I was able to delve very deeply into the humanity of these people who are considered to be on the margins of society, just as I am interested in the question of social class between the working class and the bourgeoisie and their being in opposition.

The femminiellə are firmly rooted in Neapolitan culture. They talk about the flesh and how they want to dress; it is something that is outside the bourgeoisie and that concerns all men and all women. We impose rules on ourselves, but in fact, we don't give a damn. We eat, live, die together, and even celebrate together.

A matter of joy shines through and is very inspiring from the whole movement. I don't know if you can call it a femminiellə movement, but that's how you keep a culture alive, and to do that, you have to come back down.

Marea: What will you take with you from this residency?

Clémentine: The exciting thing about this residency is the fact that I shared it with Paco and also with you. I felt that I remained very open and didn't divide my work and my daily life. So, I actually have the impression that I managed to put myself in a state of mind where I was very open.

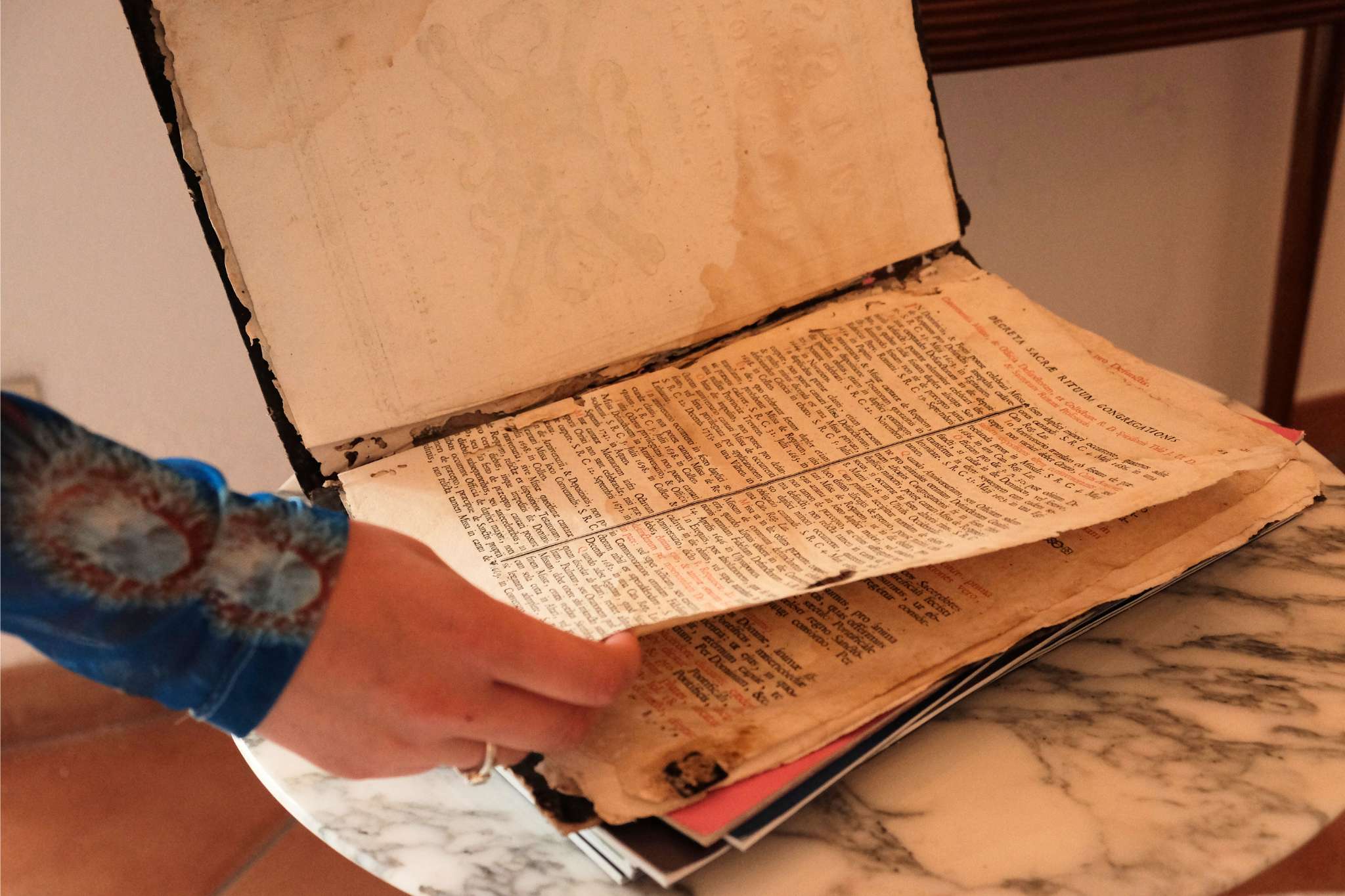

There is an excellent porosity between what you create in a given moment and the discussions you can have; it was a succession of fortuitous cases. Paco and I found a Latin book in Casa L'Orto. It is very, very old, almost torn, a bit burnt. I don't know what century; it is a religious funerary collection. So they are prayers for the dead, and my book has a lot to do with death because it tells the story of the death of a grandmother and the seven days following this event.

When I saw this book, there was a connection with my presence here, and Paco also found some of his music within this book. We both questioned what influence the things we experienced could have on our work without sharing too much about what we were doing. We never explained our processes and the themes we dealt with to each other, so it was a bit of a surprise in the end. But I really remember this porosity, all the coincidences that happened with the healers we went to see, with the grandmother removing the evil eye. A lot of coincidences.

Marea: Speaking of female healers, we met the Agerola healers who guard the knowledge and know-how of using medicinal herbs that grow wild in the area. What did you remember from that meeting?

Clémentine: It was a somewhat intimidating encounter. I was afraid to go and see the healers because I was aware that they were hands down and practiced with a sense of fear. And I got confirmation by talking to them. And this happens when you discover potentially uncomfortable things, even from a medical point of view. I think about how people are treated and cared for and how word of mouth gets around; it's a secret. It's passed on within the family, often between women, even if there was a healer among them.

But here's what I remember: the fear and the power, the silence and the enormous impact their action can have on so many people because they told us that they had healed thousands of people. There, that is the magic of what we do in secret. It has excellent power, which is preserved but which can also be lost. There is the question of transmitting the knowledge associated with these herbs.

Some herbs are wild, and this raises many thoughts for me, also in terms of the ecology of the land. Wild herbs cannot be cultivated, so what happens if it gets too hot, if there are over-exploited places, or if the land is destroyed? Here, these questions come back and are connected to my book. Can nature and what we do not have the power to control save us?

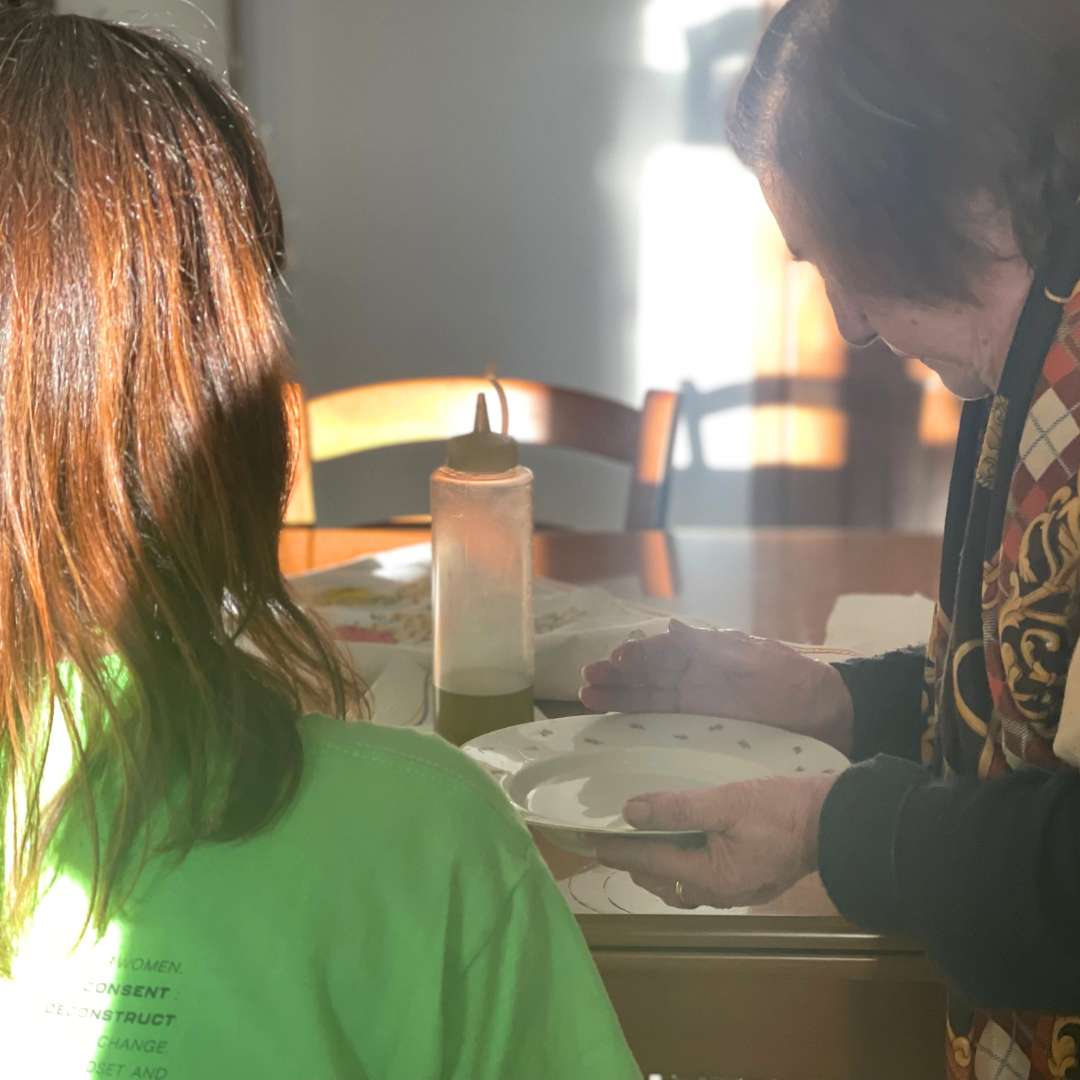

Marea: We went to visit Nonna Teresa, one of the elderly women in the village of Praiano, who can remove the "malocchio" (the evil eye), the malefic power of some people's gaze that can cause adverse effects on the person being observed. What was the experience like?

Clémentine: The malocchio is something quite familiar to me. So, I was inquisitive to see how the practice occurs around here. Do you have an evil eye? How do you remove it? Watching the process from a plate, the water, the oil, listening to things I didn't understand because I don't speak Italian. I didn't understand, but something very powerful was already happening, and I was happy to experience that moment.

It wasn't just about talking to Grandma Teresa but about being active in something. It is not foreign to me because, in my family, there are several practices perceived as dark, occult, and spiritual, not from a religious point of view. Around me, many of my mother's friends are mediums who draw cards and play with pendulums.

We do it often, and I believe in it a lot, but I wonder if it's real. But because I believe in it, I decide that it is. So, it's something I also practice daily on a personal level. I was pleased to see how this practice happens here in Praiano.